Climb on board for the latest Memory Lane feature, this week with thanks to Braunston Marina.

It came to light during the recent cataloguing of the historic Sitwell family library in Northamptonshire.

Tim writes "Having taken an interest in local canal history since I acquired Braunston Marina in 1988, one thing has always struck me – just how little recorded history there is. This is despite the pivotal transportation role that the canals played in the first industrial revolution - with Braunston at the very heart of the canal network. So I was fortunate to be contacted by Susanna Sitwell, with an exciting new canal find. Susanna is one of my wife’s regular tennis-four, and thus knew of my canal interest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer late husband’s family had lived as squires at Weston Hall near Towcester since 1714 - the last year of the reign of good Queen Anne. Her husband’s father, aunt and uncle, Sir Sacheverell, Dame Edith Sitwell and Sir Osbert Sitwell, had each been major players in the arts world in roughly the first half of the 20th century. With its magnificent rural setting, Weston Hall was very much on the cultural map – with artists such as the composer William Walton being among the regular visitors. He composed his masterpiece ‘Façade’ to poems by Edith Sitwell.

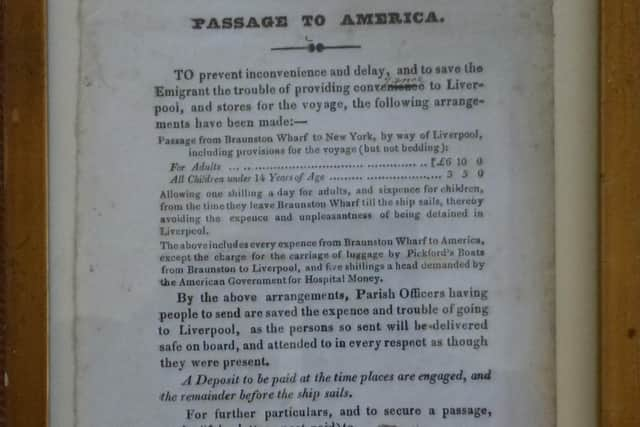

Sadly, despite the family striving to keep the house going for many years, a final decision was made in 2020 that the time had come to sell. As part of the enormous task of collating chattels collected over centuries, Susanna went through over 2,000 books in the old library. By chance she came across an amazing leaflet headed ‘PASSAGE TO AMERICA’, which she soon drew to my attention, giving me a photocopy of it.

Neither I, nor any of the canal-cognoscenti I have since shown the leaflet to, were aware that Braunston Wharf had been used as the major point of embarkation ‘to save the Emigrant the trouble of providing conveyance to Liverpool ’ We were even unaware of the wharf being used for transportation of passengers on any significant scale, and all the other intriguing bits of information the leaflet revealed. So with no apologies, it is reproduced here in full.

PASSAGE TO AMERICA

To prevent inconvenience and delay, and to save the Emigrant the trouble of providing conveyance to Liverpool, and stores for the voyage, the following arrangements have been made:-

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPassage from Braunston Wharf to New York, by way of Liverpool, including provisions for the voyage (but not bedding):

For adults………………………………… £6 10 0

All children under 14 Years of Age…………£3 5 0

Allowing one shilling a day for adults, and sixpence for the children from the time they leave Braunston Wharf till the ship sails, and thereby avoiding the expense and unpleasantness of being detained in Liverpool.

The above includes every expense from Braunston Wharf to America except for the charge of carriage of luggage by Pickford’s Boats from Braunston to Liverpool, and five shillings a head demanded by the American Government for Hospital Money.

By the above arrangements, Parish Officers having people to send are saved the expense and trouble of going to Liverpool, as the persons so sent will be delivered safe on board, and attended to in every respect as though they were present.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA Deposit to be paid at the time places are engaged, and the remainder before the ship sails.

For further particulars, and to secure a passage, apply (if by letter, post paid) to E. Billing, Rose & Crown Inn, Northampton.

The following is a list of provisions for the voyage to New York.

For each adult: 56lbs. Biscuit 126lbs. Potatoes 30lbs. Beef and Pork

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad10lbs. Dried Cod-fish 3lbs. Butter. 10lbs. Flour or Oatmeal.

Half the above quantities for each child under 14 years of age.

Besides running that house and playing tennis, Susanna has always enjoyed her history. In 2012, she enrolled on a course in this at Oxford University Department for Continuing Education, choosing as one of her courses, ‘Emigration and Transportation from England in the Nineteenth Century.’

The choice was deliberate, as from her own studies, Susanna was already aware of the massive social problems that occurred both locally in Northamptonshire and nearby Oxfordshire, and across England in the period post the Napoleonic wars.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite England winning the final campaign, and emerging from those wars having never been invaded - and now being the richest and most powerful nation in Europe - this success was offset by great civil unrest amongst the working classes. Unemployment was now high with the cessation of war production and the meltdown of the navy, to which was added the return of some 30,000 former soldiers from the Waterloo campaign.

Meanwhile the Agricultural Revolution, which had involved new farming methods and machinery, had continued throughout the wars apace, including an acceleration of the enclosure of the common land. Whilst food production had massively increased, the changes had resulted in vast numbers of agricultural workers losing their lands and livelihood, and with families living destitute in the countryside or being driven helplessly into the satanic overcrowded towns. Adding to the social pressures, was the explosion in population, due to a combination of improved food production, and the health of the population, including a significant reduction in infant mortality.

Pressures built up during the 1820s, coming to a head in 1830, with near civil war between the disposed agricultural workers and the land’s new owners, with their mechanized methods of agriculture. There were riots in Banbury in 1830, and gangs of former farm workers – sometimes in their several hundreds – went on the rampage, in the countryside. They were supposedly led by the mythical Captain Swing, whose exact being was never discovered, and their targets were the new farming machinery, especially the new wooden threshing machines - this despite the threat of being hung or transported if they were caught.

One immediate answer for the government to release pressure was the assisted emigration schemes. These were of some success, and by 1850 over one million people had left, largely to be replaced by fast growing population and immigration from Ireland during and after the famine of the late 1840s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were many major emigration schemes, including the 4,000 London and Essex artisans – the ‘1820 Settlers’ - who went in that year to the eastern provinces of the Cape of Good Hope. But at a local level, from the 1820s onwards – and later enshrined in the still controversial 1834 Poor Law, Parish Officers were also permitted to pay from parish funds for young unemployed families – mainly agricultural workers - to be transported free and of their own volition to the British colonies and the United States of America. The government had hoped that most would go to the colonies, but the US was the preferred destination for most of them. And hence this leaflet offering the prized New York, which was passed round the powers-that-be in Northamptonshire, including the then Sitwell ancestors.

Several fascinating insights emerge from this leaflet, and let’s take them one by one.

Where was the Rose and Crown Inn in Northampton? We have found that it was located in the then prosperous Gold Street, and that Mr E. Billing was its landlord until he died in 1839. In 1832 Mr Billing was also recorded as agent for the shipping companies Becket and Co., and Fitzhugh and Grimshaw, both of Liverpool, and his advertisement of that year says: ‘N.B. Parish Officers having people to send, may be treated with on terms of great advantage.’ We have not found just where the Rose and Crown was in that street, nor any image of it, despite the suggestion that it may have been an inn of some importance, with Mr Billing doing business well beyond the town. Today this once prosperous street is now rather rundown and seedy

What was the date of Susanna’s leaflet? We also found three other press advertisements in the Northampton Mercury, all headed ‘Passage to America’. The papers are dated variously between 23rd January, 1830 and 28th February, 1832. The other advertisements all offer ‘passage from Northampton to New York’ – the Northampton Arm was opened to the Grand Junction Canal in 1815 – so interestingly Braunston Wharf is not included, and only features once on Susanna’s leaflet. But the passage price remains at £6. 10. 0 for a much longer trip. All these other advertisements predate the 1834 Poor Law Act. But just when Braunston became the starting point and for how long is somewhat guesswork.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

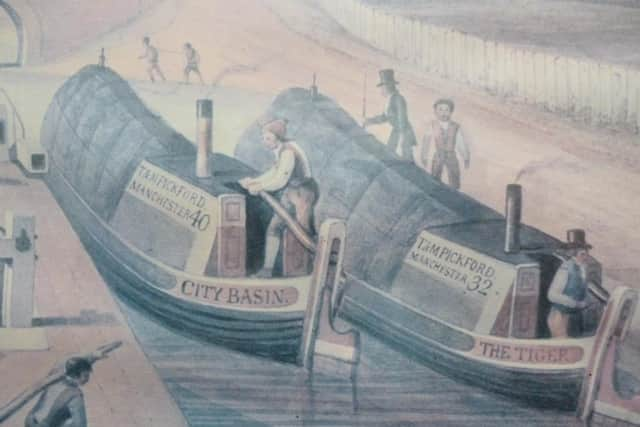

Hide AdAnd so to the carrier, ‘Messrs. Pickford’s Canal Boats’: its services were offered in all of E Billing’s advertisements, with the proviso that ‘any extra Luggage must be paid for by the Passengers’. Pickfords is one of just a handful of British companies still operating today that has been in continuous operation and under the same name for over two hundred years. (At Braunston we also claim the two hundred years of continuous operation, but under several names, including Pickfords!)

The company began in Manchester as canal carriers in 1786. Just when it opened a branch at Braunston is unknown - probably not long after the completion of the Grand Junction Canal in 1805. The Wharf was chosen for its immediate proximity to the main London to Chester Road, so the company could deal with transshipment of goods, aided by warehouses adjacent to the canal. There were also the existing dry docks, which could be used for boat maintenance. The first surviving reference to Pickford’s presence at Braunston that we have found was in 1821, when it was recorded that the company had three porters, and an agent and a clerk at the Wharf. This staffing arrangement would have dealt with the emigrants awaiting passage to Liverpool in the early 1830s. In 1820 the company had over eighty boats in their fleet and by 1838 - the year of the opening of the London to Birmingham - the number had risen to its peak of 138. Thereafter Pickfords saw the writing on the wall, and began moving its carrying onto the railways - sometimes using their own trucks. They finally ceased canal carrying in 1848. Later the company moved into road transport, in which capacity it continues to this day. When I bought Braunston Marina in 1988, and aware then of this connection, I used Pickfords to move myself and family up here from Surrey, and good services they gave us.

A fascinating and so far unexplained aspect of Susanna’s leaflet is that it, and the other advertisements we have discovered, are the only reference we have found to Pickfords carrying passengers on narrow canals – their passenger carrying on broad-beamed boats on London’s large Regent’s Canal are of course well known. Given that the passengers were penniless emigrants, and knowing of the rough conditions on the awaiting emigrant ship, it is most probable that on the narrow boats, they would have slept on planking in the base of the hold, under the rough canvas used for keeping cargoes dry. As seen from the leaflet, emigrants had to provide their own bedding. Both the narrow boats and the ships would have carried general cargoes on the return trips.

As to the length of time the run took from Braunston to Liverpool, we know that Pickfords narrow boats travelled ‘fly’ – i.e. going non-stop day and night - with what were termed ‘precious cargoes’. Assuming emigrants fell into this category, we have estimated it would have taken only three to four days to make the journey into Liverpool Docks. This assumes the horses travelling at four miles an hour, and an average of five minutes per lock.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs to the ships, in his advertisement of 23rd January, 1830, but not in Susanna’s leaflet, Mr Billing boasted that ‘Superior First-class Coppered Vessels Sail for New York every Week, Burthen, per Register, 400 Tons and upwards. Lofty between Decks, with spacious Accommodations (sic) for Passengers.’ A rival promoter of the time offered the 386 Tons per Register ‘Teviotdale’, with ‘superior accommodation (being seven feet high between Decks) and the treatment liberal’.

Much has been made of the danger of ocean passages at the time in sailing ships of about 500 tons – especially the so-called ‘coffin ships’ used for emigration during the Irish Potato Famine of the late 1840s. But there is evidence that whilst there was loss at sea, the extent has been somewhat exaggerated. In the 19th century, over one million British emigrants were successfully transported by sailing vessel to Australia alone.

A good insight into this is to make a visit to the replica ‘Jeanie Johnston’ now lying on the River Liffey in Dublin. It is a copy of the three-masted barque of 510 tons, which made its maiden voyage in 1848 from County Kerry to Quebec. In all, it made 16 transatlantic voyages to North America, averaging 47 days, and carrying some 2,500 Irish emigrants, which was achieved without loss of life. On one voyage, it carried 254 passengers. For the return voyages, the bunk arrangements were removed and stored, and the ship’s hold was used for carrying timber from North America. Later the ship was sold and converted to general cargo carrying.

So who were those penniless emigrants? We did not need to look far from Braunston. In the 1829 Parish Account Book for the neighbouring village of Grandborough, there is an entry on 14th March: ‘To James Labrum, Daniel Howkins & Daniel Hazelwood for support for their families to Liverpool £1. 10. 0. Paid James Labrum for the remains of his goods £1. 0. 0, Paid expenses at Braunston 14. 0, Paid for tea and sugar for families 4/ 10. To Mr Lea for the freight to Liverpool £9. 6. 3,’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo what happened thereafter? We have been able to pick up Daniel Hazelwood from the Mormon website, as born in England 1791 and dying in 1872, in Henderson, Jefferson Co. NY – so a good long life. Branches of both the Hazelwoods and the Howkins who remained at home, still live locally. Howkins & Harrison are prominent local estate agents, whilst Ben Howkins is internationally known in the wine trade and is a recognized leading expert on sherry. Ben was born and educated locally, going to Rugby School, and he still lives within a few miles of Braunston. Much as he has travelled the world, he says that Northamptonshire remain his home. ‘But nearly two hundred years later, and we are still an impoverished family. Nothing has changed!"

Tim would like to record his thanks to the following in strict alphabetical who helped in piecing together this fascinating story: Chris Clegg, Alice Coghlan, Jenny Coy, John Forster, Ben Howkins and Susanna Sitwell. Also for literary sources: David Blagrove’s ‘Canal History of Braunston’ and Alan H. Faulkner ‘The Grand Junction Canal’.